“I don’t care what the science says, it worked for me”

“I only believe what I see with my own eyes”

“I’ve worked with clients for twenty years, so I can say for a fact that this works”

If you really want to understand the science behind beauty products, you have to understand why science is important when it comes to figuring out what actually works. It’s time to talk about anecdotal evidence, and why we can’t rely on it.

It sounds abstract, but it’s really important to understand, because it sort of explains why we’re all here talking about science. And it applies to beauty products as well as other things in life, like medical treatments, nutrition and supplements.

Here’s the video version on YouTube – scroll down to keep reading!

What is anecdotal evidence?

Anecdotal evidence is when someone says something worked for them, or for someone they know – basically, it’s a one-off example of something working or not working.

Some examples:

- ACTION: I used this cream

- RESULT: Pimple disappears

- CONCLUSION: This cream must be great for treating pimples

- ACTION: I took a multivitamin

- RESULT: My cold got better

- CONCLUSION: Multivitamins fixed my cold

- ACTION: My grandma smoked continuously

- RESULT: She died at 92

- CONCLUSION: Smoking is fine for your health

As you can see, anecdotal evidence leads us to conclusions that can range from maybe reasonable to obviously incorrect.

We see anecdotal evidence everywhere in beauty. Testimonials and reviews are all forms of anecdotal evidence.

And anecdotal evidence isn’t just limited to regular consumers – “expert opinions”, “experience” and “case reports” can often be forms of anecdotal evidence too. Medical professionals, scientists and beauty professionals use (and misuse) anecdotal evidence as well. It’s simply part of being human.

All human beings have evolved to be subjective and prone to biases. These are distortions in our thinking that stop us from being completely objective and rational machines. These biases actually helped us survive through the ages, but unfortunately they don’t help us as much in the modern world.

What’s wrong with anecdotal evidence?

Anecdotal evidence can be very useful in some situations. If you’re going for a treatment, you probably want an experienced therapist, rather than one who’s brand new.

But the problem with anecdotal evidence is that, while it’s sometimes really useful, it isn’t reliable – as we saw earlier, the conclusions we draw from it are all over the place, and we have no way of telling which ones are good. And we, as humans, have a bias to give anecdotal evidence far more weight than it should have.

Anecdotes aren’t good enough evidence for saying a treatment caused a particular outcome. If anecdotal evidence disagrees with good scientific studies and there’s no plausible explanation for how the treatment might work, then we should go with what the science says.

Anecdotal evidence is really appealing

Unfortunately, anecdotal evidence can be incredibly convincing. It’s a lot easier to believe someone’s heartfelt story than try to understand complicated, faceless, and often scarily technical scientific data, even if there are many someones behind that data. (This is part of the reason documentaries are so compelling, and why a lot of pseudoscience promoters choose to focus on documentaries for spreading their information.)

Our love of personal stories was great for human survival. If you avoided all red berries because one person died from eating them, you end up staying alive for longer, even if not all red berries are dangerous.

But unfortunately these mental shortcuts – these cognitive biases that inform our gut feelings – also give us a distorted view of reality. We live in a much more complex world, and we need (and have) much better ways of working out what’s going on than anecdotal evidence. It can feel unnatural to ignore instincts and gut feelings, but they evolved to help us in very different circumstances to our modern world.

Being aware of our bias towards anecdotal evidence and compensating for it is valuable – we’re more aware of what actually works, making us less vulnerable to manipulation by dodgy marketing. We can make better decisions about what to do and what to buy.

Problems with anecdotal evidence

Here are some of the problems with anecdotal evidence – I’m focusing on the ones that are more relevant to beauty products.

Regression Fallacy

Thinking an action caused an effect that naturally fluctuates

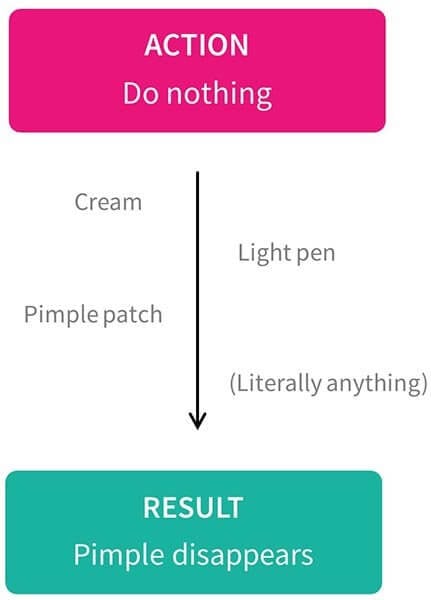

A big problem with anecdotal evidence is that things often get better on their own. Take the pimple example:

A lot of pimples tend to get better on their own in about a week (they’re self-limiting conditions). If you’re like me, you won’t deal with it until it’s ripe, at about 3 days. If I put a cream on the pimple then, and it clears up three days later, it LOOKS like it worked.

But in a different timeline, I used a light pen and the pimple also cleared up, so it looks like the light pen worked.

Or in a third timeline, I used a pimple patch and so I think that worked.

But the pimple would’ve cleared up on its own, so… none of them actually worked.

Confounding Variables

Other factors could explain the outcome

Confirmation Bias

Interpreting information to fit prior beliefs

Let’s say I used the cream, and the pimple went away faster, so I think the cream worked.

But that week I also:

- used a new cleanser

- applied some exfoliant

- went on a health kick and ate tons of vegetables

Any of those could’ve helped the pimple go away. But I only linked the cream to the pimple in my mind, because that’s what I expected to work.

Availability Heuristic

Something more easily remembered is assumed to be more important

Even worse, we tend to forget about longer-term treatments. I might’ve even started on hormonal contraceptives, and then used the pimple cream. The effect of the hormones kicked in and made the pimple go away faster than usual, but I think it’s the cream because it’s the last thing I did.

Memory Biases

Distortions in how we remember things

Another issue is that humans aren’t great at observing things. I’m sure you’ve had the experience where you and your friend can’t agree on something really mundane, like what colour shirt someone was wearing, or if McDonald’s cheeseburgers are getting smaller.

One researcher actually developed a method to make 1/3 of people believe that a made-up event happened in their childhood. They would actually tack extra details onto this false memory when they recounted it! Us humans are really good at filling in gaps with random stuff, and tricking ourselves into believing things.

Unless you’ve been really carefully measuring your pimple, you can easily trick yourself into thinking it’s getting bigger or smaller, redder or lighter – and it’s even worse if you’re not looking at it with consistent lighting, at the same time of day.

As I’ve described in The Lab Muffin Guide to Basic Skincare eBook, there are a few ways to make your observations as objective and accurate as possible, like taking careful photos and keeping a skin diary. But while these can help you trick yourself less, it still isn’t foolproof.

Post-Purchase Rationalisation (Choice-Supportive Bias)

Ignoring problems to justify something you bought

If you spent a lot of money on the cream and you really want it to work, you might even subconsciously trick yourself into believing it worked – forgetting all the times you used it and it didn’t work. And this effect can be bigger for more expensive products – you don’t want to think you’ve wasted your money on a useless product.

Science sets up fair tests

So how could we tell if a cream REALLY helps clear up pimples? The best way is to set up a fair test, specifically comparing the pimple cream with no cream at all.

Control variables

We’d ensure that everything else stayed the same. For example, if you had two identical pimples, then everything you ate would affect both pimples equally. You could make sure you use every other product equally on both, or stop using anything else.

Repeat and remove outliers

If the pimple cream worked, we’d also want to make sure it wasn’t a one-off fluke where the lighting made the pimple look like it was smaller, or the pimple was less severe than usual, or the person scratched one pimple in their sleep and not the other.

Instead of just trying the cream on one pimple, we could try it on lots of pimples, then get rid of the one-off fluke results.

Use a comparison (control)

If we wanted to test a specific ingredient, we could even make two creams – one with the ingredient and one without – and test them against each other.

Blinding

To make sure the people recording the results aren’t biased, we could label the creams A and B, so they wouldn’t know which cream was which.

And that’s pretty much what science does – it sets up fair tests that get rid of as much human subjectivity and bias as possible.

Problems with scientific evidence

So that’s why scientific evidence is better than anecdotal evidence. If science says one thing, but anecdotes say another, we should go with what the science says.

But a big issue with skincare is that there aren’t that many good quality scientific studies around. The best ones are for prescription products, or for more serious skin conditions like rosacea.

- A lot of studies aren’t fair tests

- They might only test one specific product that’s too different to the product you’re using to draw a convincing comparison (low generalisability)

- They didn’t test it on enough people to say much one way or another

If we don’t have a lot of science to guide us, that’s when reviews and personal experience become more valuable, since it’s the best we have – but given how subjective and prone to biases this anecdotal evidence is, there are a few things we should keep in mind so that we’re not misled.

Problems with reviews

Reviews can be a fantastic resource for finding products that might work well for you. But it’s important not to believe every review you read. As well as all of the problems with anecdotal evidence mentioned earlier, there are some extra things to consider:

Many companies post fake reviews of their products. They might pay someone to churn out a bunch of positive reviews and post them online.

Even if they aren’t fake, reviews can also be incentivised. If a company gives out free samples, or if they pay someone to review their products, this conflict of interest might mean that the review is more favourable than it might otherwise be.

But at the same time, just because someone was paid or received free product, it doesn’t mean that it’s the only reason the review is positive. And even when someone is reviewing a product they bought themselves, it doesn’t mean it’ll be completely objective – there are issues I mentioned before like confirmation bias, when someone’s more likely to see a change if they’re expecting a change, and post-purchase rationalisation, especially if it’s an expensive product.

Related post: Thoughts on Sponsorships, Disclosures, Product Samples, Bias etc.

There are also issues if you’re looking at multiple reviews.

You might see a lot of very good reviews, or very bad reviews, and this is because humans are… kind of lazy. Unless something works really well or really badly, we’re not likely to go to the trouble of writing a review. This reporting bias means that we often only see extreme results in reviews, so we can’t get a very good idea of how likely a good result will be – how representative those reviews are. If we see 10 rave reviews, we don’t know if it’s a niche product where all 10 people who tried it loved it, or a mediocre but popular product that thousands of people tried but it only worked well for 10.

Very few people update their reviews, so we also don’t know if the product still worked or they changed their opinion later after trying the product out more.

Humans are also better at remembering recent things more clearly, so products with immediate results will probably get better reviews than one that has longer term effects, even if the slower product has a larger impact (availability heuristic).

If you’ve ever read skincare reviews, you’ll know that different people can have very different experiences with the one product. In scientific studies, the people studied are usually very specifically described, e.g.

in Cincinnati, OH, U.S.A. from February to August 2008 in 196 women aged 40–65 years who were neither pregnant nor lactating. Eligible subjects had Fitzpatrick skin types I–III and moderate to moderately severe periorbital wrinkles on both sides of their face.

This means you can work out how close you are to the people that it worked on. But in reviews, you often know very little about the reviewer.

(These are some of the reasons behind the saying: “The plural of anecdote is not evidence.”)

When to use anecdotal evidence

So where does this leave us as beauty consumers? This is where I talk about what I personally think a sensible approach is – you might disagree and that’s perfectly valid.

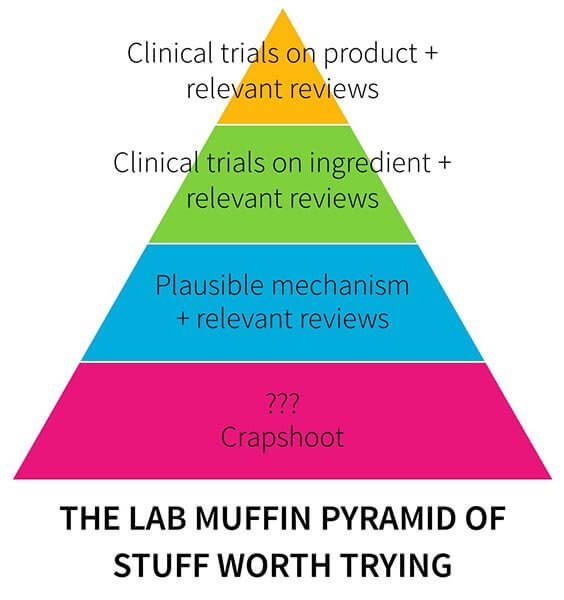

- Your best bet for products that will work for you are those that have enough scientific evidence to back up its effectiveness, but also have a large number of reasonably objective positive reviews from people in a similar situation as you.

- If there isn’t any scientific evidence for that exact product, then you want some evidence for its active ingredients.

- If you don’t have that, then you’d want there to be a plausible mechanism – a scientifically sound explanation for how it could potentially work – and no compelling scientific reasons why it wouldn’t work.

If anecdotal evidence disagrees with the scientific evidence, then you should go with what the scientific evidence says.

The higher the risk – both health-wise and in terms of budget – the stronger the evidence should be.

Anecdotal evidence is still useful in helping us decide which products to try – as long as we keep in mind the limitations, and avoid treating it as proof of something working.

This was so informative and I appreciate the sound advice as I am easily persuaded. Thanks so much.

Such a great post and a really important message! Thank you Michelle ?

This is amazing! I have wanted to try to write a post like this for so long and could never explain it without starting to rant too much you nailed it ? thank you for helping to share easy to understand science for people who don’t work in the industry (and sadly a lot of people who do but have been only taught basic cosmetic chemistry and then solely rely on education from product reps and then spread the misconceptions under the title of expert beauty therapists) Thank you for the time you devote to your videos and posts ??

I truly believe if everyone is taught how to analyze data and understand how to apply a more scientific base to what they choose to believe it would change the world so much for the better not only to be able to cut through the bullshit marketing in beauty but in everything we do and choose to believe ?

Lyndall Innes

Dermal Therapist, Skin Nerd & Lover of Education.

Just want to point out that some companies that pays for research might produce a biased result. There is too much money involved in developing and testing products so companies rack up a bill that needs paying one way or another and they are therefore slow to dismiss a failed product. They tweak the research, instead, to show what they want it to show and get a green light for distributing it. I read about some of these companies in my business ethics class. One of them was an anti-depressant that only made people worse. Thalidomide might have been another one with sad consequences. Therefore, I it is also good to check who’s funding the research and why. The science might look sound but some results can have been left out or some numbers given far more importance than what’s fair.

That is why I try to review every product I used – to not only talk about the great and disgusting ones, but to add to the search of people looking for that specific product. Means I don’t accept much skincare PR anymore, otherwise I couldn’t use the products long enough.

A very thorough look at why we need to base our decisions on science and the ingredients. But the other thing is that everyone’s skin is different, so what works for one person might not work for someone else. In my routine, I try different products one at a time to see if they have a different effect. But you are right – there are so many other factors that could influence the results – diet….exercise…mood…the weather! In the end I try and make my ‘trial and error’ approach as scientific as it can be. Half the fun is experimenting 🙂

I hate when people tell me ‘This item is amazing, it’ll fix your skin, it did mine.’

We all know what works for one, may not for another.

Stephanie Rose | http://www.blondedaisychains.co.uk

Love this article. Very insightful and helpful.