Alcohol (ethanol, ethyl alcohol, SD alcohol or alcohol denat) is one of the most controversial ingredients in skincare. You might’ve heard that it speeds up aging, kills skin cells, and creates inflammation. But what do the studies actually tell us?

Stephen (@kindofstephen) and I have been working on this topic for a long time, and we hadn’t decided on the right format to present the information – we ended up landing on this video. Hope you enjoy it!

Check out the YouTube video here. It’s also below in text form if you prefer reading.

What Is Alcohol?

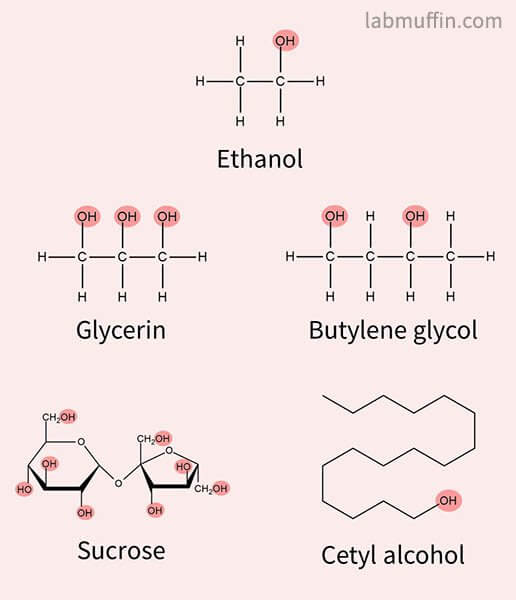

In chemistry, an alcohol is any carbon-based compound that contains an OH or hydroxyl group.

So for example, all of these chemicals are alcohols:

But just because they’re alcohols doesn’t mean they all have the same properties on your skin:

- Glycerin and glycols are humectant moisturisers that hydrate skin

- Sucrose is table sugar

- Cetyl alcohol is a fatty alcohol moisturiser that feels oily

So yes, some alcohols can be beneficial for your skin.

But when people talk about alcohol in skincare, they’re mostly talking about ethanol, which has a reputation for being drying and irritating.

What Is Ethanol?

Ethanol (ethyl alcohol, SD alcohol or alcohol denat) is mostly the same alcohol that’s found in alcoholic drinks.

Denatured alcohol, often listed on skincare ingredient lists as Alcohol Denat or SD Alcohol (SD stands for specially denatured) is simply ethanol with a small amount of an extra ingredient (e.g. pine oil or methanol) mixed in to discourage people from drinking it.

Why is alcohol in skincare products?

Ethanol is included in skincare products for a few different reasons.

Dissolves ingredients

Ethanol is a good solvent that can dissolve some things that water can’t. It’s often used in fragrances since many fragrance oils and esters don’t normally dissolve in water, but can dissolve in alcohol.

Some actives in skincare are too oily (non-polar) to dissolve in water, but ethanol can still dissolve them – one example is salicylic acid (beta hydroxy acid).

A lot of skincare products use glycols as solvents instead (propanediol, propylene glycol), but these aren’t as volatile so they don’t evaporate as easily, and can leave a shiny look on the skin (which can be good or bad depending on your preference).

Plant extracts

Plant extracts

Ethanol is used to help extract ingredients from plants, again due to its superior solvent abilities compared to water.

Cleaning agent

In older toners and makeup removers, alcohol is sometimes used to help remove lipids, oils and waxes from the skin. It can also be used to prepare skin for treatments like peels.

Preservative

A high concentration of alcohol can be used as a preservative, although this is not very common anymore.

Improves application

Ethanol’s ability to evaporate quickly (its volatility) means that it can help improve product application. It can help formulas spread and set quickly, and give a cooling effect. This is often used in sunscreens to help make their textures lighter.

Skin penetration enhancer

Ethanol can help some active ingredients get through skin deeper, and in a higher concentration to increase their effectiveness.

So alcohol is pretty useful in products… but is it harmful?

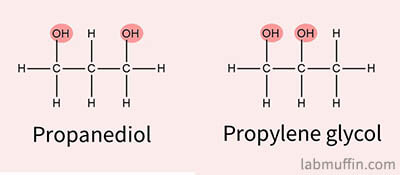

In vitro studies can’t be directly applied

There are lots of in vitro studies where the effects of alcohol on isolated cells or isolated skin samples were studied.

And the results of these can sound quite scary: alcohol can make skin cells die (apoptosis), produce inflammatory signals, denature proteins and slow down enzyme activity. And we know that alcohol can also kill bacteria.

But applying alcohol on skin is very different from pouring alcohol onto naked cells in a dish, or onto a bacterium made of one cell.

The stratum corneum is an excellent barrier

Our skin is covered by the stratum corneum, a fantastic barrier between our living cells and the outside world. It contains 15-20 layers of dead skin cells, toughened with keratin, and they’re surrounded by intercellular lipids that prevent substances from passing through.

So for ethanol to affect living skin cells like it does in in vitro studies, it has to make it past the stratum corneum to the living cells in a high enough concentration. But it has a lot of trouble doing this because…

Ethanol is very volatile

Most in vitro studies used relatively low concentrations of ethanol – somewhere around 0.5%. But they also left the cells in contact with ethanol for a long time, usually 24 hours, in a sealed container where the alcohol couldn’t evaporate.

However, when ethanol is applied to skin, like in a skincare product, it evaporates.

One study applied 100% ethanol to discs of pig skin (which is very similar to human skin). They found that half the applied alcohol evaporated after 10 seconds, and less than 3% of what’s applied stays on or in the skin (there are issues with the 3% – some of it was suspected to have leaked through the equipment, so the real value could be far less).

So if you’re using a skincare product – with a maximum of about 10% alcohol in it – more than 97% of that evaporates. For your skin cells to experience the conditions in in vitro cell studies, the rest has to then travel into your skin and stay there at a high enough concentration for quite a long time, without being metabolised, or diffusing away into the rest of your body. 0.5% ethanol suddenly seems a lot less achievable.

Due to these reasons, we can’t immediately apply these to when we use alcohol in skincare. The most relevant studies would be the ones looking at alcohol being applied to human skin, and seeing what happened.

Clinical trials

As I’ve mentioned before, it’s hard to find skincare studies because research needs to be funded, and unless there’s a good public health or commercial reason, there’s no real incentive to fund expensive clinical trials.

Luckily, there’s a situation where people DO end up applying and reapplying alcohol on their skin multiple times a day. That’s in healthcare, where alcohol-based hand rubs (hand sanitisers) are used by healthcare workers to prevent spreading of diseases.

Nurses in particular need to disinfect their hands between patients to prevent transmission of disease. This adds up – one study found that nurses had to clean their hands an average of 55 times a day. Lots of nurses end up with cracked skin, irritation, blisters and rashes from this repeated cleaning. It’s been found that skin irritation makes people less likely to follow hand hygiene procedures, so there’s a good reason to research it.

The main methods for disinfecting hands are hand washing with soap and water and with alcohol hand rubs. There’s been quite a few clinical studies comparing the effects of soap and water versus alcohol hand rubs, and between different hand rubs formulas, on skin irritation, dryness and so on.

What do the clinical trials tell us?

They pretty much tell us that using a massive amount of alcohol on your skin… doesn’t have a huge impact.

Most of these hand rub studies were performed quite similarly:

- Alcohol-based hand rubs or mixtures of alcohol and water (generally containing 60-100% ethanol concentrations) were used.

- These were rubbed into the inner forearm multiple times a day, to mimic the frequency of hand hygiene procedures for nurses (5-100 times a day, depending on how intense the experimenters decided to go, or how much stamina their arms had perhaps).

- This process continued for 7-14 days.

- Measurements of skin condition would be taken every few days.

- Some studies also included repeated cleansing, again to mimic a typical healthcare worker’s exposure to additional irritation (surfactants in cleansers can be very irritating).

So based on the much more extreme conditions in hand rub studies compared to skincare, it’s likely that whatever effects were found would be a more extreme version of what happens when we apply beauty products like sunscreens and moisturisers typically containing, at most, 5-10% ethanol.

Here’s what the studies found regarding some of the major concerns about alcohol in skincare:

Inflammation

Inflammation isn’t good for your skin – it’s linked to aging, acne, rosacea and all sorts of other issues. And in in vitro studies, alcohol seems to be able to cause inflammatory markers to be released, although this doesn’t always seem to be the case. But does this carry through to topical alcohol on skin?

In hand rub studies, inflammation was measured by looking at skin redness (inflammation causes increased blood flow).

In several studies, scientists found that ethanol didn’t seem to be linked to a change in redness, compared to no ethanol:

- Cartner et al. (2017): 70% ethanol caused no statistically significant changes in redness with 20 or 100 daily applications for 14 days, compared to water

- Löffler et al. (2007): 80% ethanol rolled on arm 50 times over 5 minutes, twice a day for 7 days caused no changes in redness, compared with water

Skin barrier disruption

In vitro, on isolated skin samples, enzymes that are important in skin shedding and production of lipids can be disrupted by ethanol, so they don’t work as well. If this occurs in skin, then the stratum corneum (responsible for most of the skin’s barrier function) could work less effectively.

There are also some in vitro studies that suggest that ethanol can cause temporary lipid disorganisation, or lipid extraction (removing lipids from skin). It’s thought that these effects are how ethanol helps ingredients penetrate.

But these findings aren’t consistent – many times even with really long exposure to alcohol there are no big changes negative effects in these studies on skin samples. And many of these studies do actually point out that these conditions don’t really reflect how we use alcohol in skincare.

For example, a study that observed lipid extraction kept skin in contact with pure ethanol in a sealed container for half an hour – very different from the situation in a skincare product where we’d expect ethanol to evaporate quickly.

In the clinical hand rub studies, again – skin barrier disruption doesn’t seem to be a big issue.

Skin barrier in these studies was measured using TEWL (transepidermal water loss – a more disrupted barrier allows more water to escape).

In multiple hand rub studies, changes in TEWL were only minor. There was a measurable difference in the Cartner study, but only when ethanol was applied 100 times a day, not 20 times.

- Cartner et al. (2017): 70% ethanol caused no statistically significant changes in TEWL with 20 daily applications for 14 days, compared to water; but there was a statistically significant difference for 100 daily applications

- Löffler et al. (2007): 80% ethanol rolled on arm 50 times over 5 minutes, twice a day for 7 days caused similar changes in TEWL compared with water

- Kramer et al. (2002): TEWL didn’t change significantly when hand rubs containing 60–80% ethanol were applied 20 times on Day 1, then 5 times a day on Days 2–7

Skin dehydration

One effect that can seem to happen with alcohol is skin dehydration. There have been mixed results in clinical studies – some have found that alcohol decreases skin hydration, while others haven’t.

- Cartner et al. (2017): 70% ethanol caused no statistically significant changes in capacitance with 20 or 100 daily applications for 14 days, compared to water

- Löffler et al. (2007): 80% ethanol rolled on arm 50 times over 5 minutes, twice a day for 7 days caused a decrease in skin hydration compared with water – interestingly, this effect was greater for lower ethanol concentrations

- Kramer et al. (2002): Superficial sebum content didn’t change significantly when hand rubs containing 60–80% ethanol were applied 20 times on Day 1, then 5 times a day on Days 2–7

However, another study found that adding moisturising ingredients like glycerin and fatty alcohols to a propanol-based hand rub could decrease dryness and irritation (propanol is more drying and irritating than ethanol). These sorts of ingredients are almost always found in skincare products containing ethanol.

Then why does it sting?

One reason that we tend to be a bit scared of alcohol is that sometimes it can cause a painful stinging sensation, especially on broken skin.

But multiple studies have concluded that the stinging from alcohol – the feeling of irritation – actually didn’t reflect what was happening physically to the skin.

Alcohol does tend to sting your skin if it’s already damaged – the alcohol can soak into the nerve endings and cause the stinging sensation, even if it isn’t causing any additional damage. It’s like a more intense version of when water gets into a paper cut.

So what does this mean for alcohol in skincare?

The clinical studies on alcohol-based hand rubs aren’t done under the same conditions as we’d use alcohol in skincare:

- The studies are mostly on arm skin, which is thicker and less sensitive than facial skin

- Most studies only lasted a couple of weeks at most

- Far higher concentrations of alcohol were used than in skincare

- Alcohol-containing products many more times a day than in a skincare routine

- Some studies also included very frequent cleansing in their procedures, compared to 1-2 times daily in skincare

- In skincare products, there are other ingredients like glycerin which would decrease any skin dryness and irritation caused by alcohol

So overall, to us, the evidence seems to point towards alcohol not being much of a concern in skincare, given how small the impact is with far more extreme conditions in alcohol hand rub studies.

References

Clinical alcohol-based hand rub studies

Cartner T et al., Effect of different alcohols on stratum corneum kallikrein 5 and phospholipase A2 together with epidermal keratinocytes and skin irritation (open access), Int J Cosmet Sci 2017, 39, 188-196. DOI: 10.1111/ics.12364

Kampf G et al., Emollients in a propanol-based hand rub can significantly decrease irritant contact dermatitis, Contact Dermatitis 2005, 53, 344-9. DOI: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00727.x

Kramer A, Bernig T & Kampf G, Clinical double-blind trial on the dermal tolerance and user acceptability of six alcohol-based hand disinfectants for hygienic hand disinfection, J Hosp Infect 2002, 51, 114-20. DOI: 10.1053/jhin.2002.1223

Löffler H et al., How irritant is alcohol? Br J Dermatol 2007, 157, 74-81. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07944.x

Lübbe J et al., Irritancy of the skin disinfectant n-propanol, Contact Dermatitis 2001, 45, 226-31. DOI: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.450407.x

Winnefeld M et al., Skin tolerance and effectiveness of two hand decontamination procedures in everyday hospital use, Br J Dermatol 2000, 143, 546-50. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2000.03708.x

Boyce JM, Kelliher S & Vallande N, Skin irritation and dryness associated with two hand-hygiene regimens: soap-and-water hand washing versus hand antisepsis with an alcoholic hand gel, Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2000, 21, 442-8. DOI: 10.1086/501785

Other literature on hand rubs

Azim S, Juergens C & McLaws ML, An average hand hygiene day for nurses and physicians: The burden is not equal, Am J Infect Control 2016, 44, 777-81. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.02.006

Bianchi J, Page B & Robertson S, NHS Education for Scotland, Hand dermatitis: A pocket guide for health care workers, 2014.

Visscher MO & Randall Wickett R, Hand hygiene compliance and irritant dermatitis: a juxtaposition of healthcare issues, Int J Cosmet Sci 2012, 34, 402-15. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2012.00733.x

Volatility of ethanol on skin

Pendlington RU et al., Fate of ethanol topically applied to skin, Food Chem Toxicol 2001, 39, 169-74. DOI: 10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00120-4

In vitro, model systems, sealed chamber studies on the effects of alcohols

Ockenfels HM et al., Ethanol enhances the IFN-gamma, TGF-alpha and IL-6 secretion in psoriatic co-cultures, Br J Dermatol 1996, 135, 746-51. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1996.d01-1073.x

Goates CY & Knutson K, Enhanced permeation of polar compounds through human epidermis. I. Permeability and membrane structural changes in the presence of short chain alcohols, Biochim Biophys Acta 1994, 1195, 169-79. DOI: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90024-8

Neuman MG et al., Ethanol signals for apoptosis in cultured skin cells, Alcohol 2002, 26, 179-90. DOI: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00198-2

Bommannan D et al., Examination of the effect of ethanol on human stratum corneum in vivo using infrared spectroscopy, J Control Release 1991, 16, 299-304. DOI: 10.1016/0168-3659(91)90006-Y

Van der Merwe D & Riviere JE, Comparative studies on the effects of water, ethanol and water/ethanol mixtures on chemical partitioning into porcine stratum corneum and silastic membrane, Toxicol In Vitro 2005, 19, 69-77. DOI: 10.1016/j.tiv.2004.06.002

Moghadam SH et al., Effect of chemical permeation enhancers on stratum corneum barrier lipid organizational structure and interferon alpha permeability, Mol Pharm 2013, 10, 2248-60. DOI: 10.1021/mp300441c

Kwak S et al., Ethanol perturbs lipid organization in models of stratum corneum membranes: An investigation combining differential scanning calorimetry, infrared and (2)H NMR spectroscopy, Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1818, 1410-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.02.013

Plant extracts

Plant extracts

Oh my, I just searched about alcohol or Ethanol in particular yesterday.

I was in doubt as a product that I want to buy has Ethanol in it. I found some infos and it’s so mixed. Well, mostly said it’s not good, it’s bad bla bla but doesn’t explain further. Some also said it’s kinda okay but still saying it’s better not to and just avoid it altogether.

I tried to look up the research myself, but as a language major, everything just went over my head lol

Then labmuffin came in rescue! Imo, your explanation is so clear and simple to be understood. I really love this blog and the youtube channel despite just found them few times ago.

Thank you so much for the article and knowledge ! 🙂

Always look forward to your posts. I really learn a lot. I only recently started researching skincare, after I turned 47. Better late than never!

Such an amazing website and thanks for sharing good knowledge

this post came at the best time. I have been wondering why alcohol in skincare was so bad yet so widely used. Thank you, I love learning about the science background of ingredients, and your writing style makes it easy to understand.

Ps. I love your skincare myths busted vids

Thank you Michelle and Stephen!

I especially enjoyed this video and article with all the explanations and references. It seems that the skincare community and general public as a whole is taking a reductionist view in focusing on individual ingredients as good or bad vs looking at the performance of the product as a whole, or its use in combination with other products. It seems to me that formulation would be king – the same exact ingredient in different products can have a different result, depending upon what combined with, and how processed.

Kind of like cooking:)

I definitely want to see more from you and Stephen together, and miss that he’s not updated his blog lately. I’m glad your videos have a permanent home here. I’d like to know more about how ingredients are sourced, produced, and processed – under heat, cold, spun at high speed, etc – that sounds fascinating.

Thank you so much for this thorough analysis based on scientific evidence. You have put my mind at rest after weeks of fretting about alcohol in some of my skincare products, having read so much online claiming it ages and damages skin, including websites like Paula’s Choice, which is so influential.

Thank you for putting in the effort to read the scientific literature, and then summarising it clearly in terms a non science background person like me can understand.

Great piece of work. Thank you so much for all you share with us Michelle, so easy to follow and understand throughout the whole piece and great comparison with the clinics studies etc.

Hi, I enjoyed your post as it was a step for me in the direction of chilling out about alcohol in skincare. *But*, some things didn’t add up for me and I was wondering if you could help clarify them.

1) It says that one of the purposes of alcohol is as a penetration-enhancer, getting the good stuff in *deeper*. And then there’s a lot of talk about almost all of it evaporating into the air within seconds. So how is it then able to *get in deep* if it’s evaporating that quickly; for sure then at least *some* of it is going *really into* the skin, no? It reads a bit contradictive to me.

2) The studies didn’t seem to find any alarming damage being done to skin by even large amounts of alcohol, but the main motivation to do the studies was because nurses tend to have very damaged skin on their hands because they have to disinfect 50x a day. If they got to blistery hands with disinfectants, then how is it not skin-damaging? Or is it understood that all the nurses got their skin problems exclusively from over-washing with soap and water?

I recently ran across the Paula’s choice website for the first time, and read around a bit, and she is *really* pushing the harmful effects of alcohol. (Got *me* convinced for sure..) One of her reasons is that by being a disinfectant, it also kills the valuable bacteria that live on our skin, ‘the microbiome’ I think she called it. Is there some value to that claim?

P.S. Thanks for the party-hat tequila-eager face, it cracked me up :).

1) Part of it is just solubility, and part of it seems to be that it disrupts the dead stratum corneum enough to let the ingredients penetrate better (the top layers of skin are dead, so penetration enhancers don’t need to touch living cells to work)

2) It seems like most of the damage was from soap and water – in experiments (and I’ve heard this anecdotally too) nurses who switch from soap/detergent to alcohol hand rubs see an improvement in hand dermatitis.

It’s difficult to work out what’s going on with the microbiome (it seems like all products disrupt it to some extent), but low amounts of alcohol like in skincare products won’t be enough to disinfect your skin (you need about 60% – hence all the fuss about hand sanitisers that weren’t powerful enough to work, and how you couldn’t disinfect your hands with most types of drinking alcohol). Preservatives in beauty products would have a much larger impact than alcohol in skincare products (don’t avoid those though).

Thanks for answering. I think I got it. By “part of it is just solubility” I suppose you mean that alcohol works as a solvent for some other active ingredient, and by dissolving this ‘thing’ into it, a new chemical compound is created, that isn’t as drying when it sinks deep down? (I sound a bit off to myself, seeing it ‘out loud’, but it’s how I imagine it). And yes, I remember you writing about your mom being a nurse. (I’ve been combing through your blog for a while, never been into skincare before; got you to thank for now having a bathroom cabinet brimming with products and using them with scientific understanding. My wallet would prefer the word ‘blame’, but screw that whiny guy.)

I gotta say though, I keep my toaster *right* next to my stove (this only sounds like a weird non sequitur, I have a point I swear) which means that it gets regularly splattered with oil. I clean it every [-too embarrassed to divulge -amount of time], and just recently I went for it, and wiped it hard with those household disposable wet wipes with surfactants, and though I wiped off the stains, it remained very slippery-greasy. I then decided to dip a cotton pad in some vodka-level drinking alcohol and wipe it, and *boy* did it degrease it! This little ‘experiment’ made it very hard for me not to see Paula B’s point of view about alcohol and its ‘stripping’ qualities. With all due respect to the studies listed, it’s very easy for me to imagine that my current BHA toner with salicylic acid listed *after *alcohol would do the same to the lipid-y stuff on my face. I also can’t help but wonder if forearm skin (where the experiments were conducted) has the same sebaceous gland activity, as I can’t ever remember my non-face skin feeling oily, so maybe it also reacts differently to the drying effects of alcohol? I do hope, however, that moisturisers with some alcohol (serving as penetration enhancer) act differently because you don’t ‘wipe off’ anything, so it doesn’t physically *remove* natural lipids from your face, if that makes any sense outside of my head..

All in all, I can totally see why it’s such a controversial ingredient.

The alcohol doesn’t react with the compound, but it keeps the compound dissolved until it absorbs.

If you’re wiping, that’s a different story, since the oil can come off onto the wipe. But if you’re applying a regular skincare product without the wipe, there’s nowhere the oil can go so it stays on skin.

Forearm skin might potentially be different to face skin, but at the same time it’s being put through much harsher conditions (20-100 applications a day).

Hi Michelle,

I really enjoy your content, so thanks a lot for your work! 🙂

I’m currently using the la Roche Posay ultra SPF 50+ sunscreen on a daily basis which contains around 10% alcohol I think (and quite the same amount of glycerin I guess?). I’m wondering if this amount of alcohol in a creamy sunscreen formula is still as volatile as in a 100% alcohol application?

Thank you!!

I’m so glad someone is doing research on this topic! I’ve been wondering for a while now how bad alcohol is in skincare. Thanks for the video!