One of the big misconceptions about sunscreens is how they work, in particular chemical and physical sunscreens. All sunscreens work mostly by absorbing UV and converting it to heat.

I’ve talked about this a whole bunch of times before, and I recently did a deep dive about the mechanisms behind how chemical and physical sunscreens work.

Related post: How Do Sunscreens Work? The Science (with video)

But then I realised I could actually measure the heat involved, and maybe it would be a bit more convincing if we could see some real numbers…

The video is here on YouTube, keep scrolling for the text version…

How much heat is involved, anyway?

Both chemical and physical sunscreens mostly work by absorbing UV and converting it to a harmless amount of heat. Physical sunscreens also scatter about 5% of incoming UV.

The sun’s energy is also about 53% infrared which converts heat directly on our skin, and only about 3-7% UV. So if most of that tiny amount of UV is converted to heat, and there’s only a small amount of difference in that tiny amount of UV, there really shouldn’t be much of a difference.

But some people have questioned whether that tiny tiny amount is enough to make a difference, so I decided to test out what happens in reality.

Cconveniently I found out that my boss Alex – a former optics professor – has an IR camera. This takes photos that show things with different temperatures as different colours, and it can measure down to a 1 degree Celsius difference. So I convinced him to help me do some measurements with sunscreen to see if we could see anything interesting, and we went off to a rooftop garden in Sydney during spring with a bunch of different sunscreens.

Sunscreens on Skin

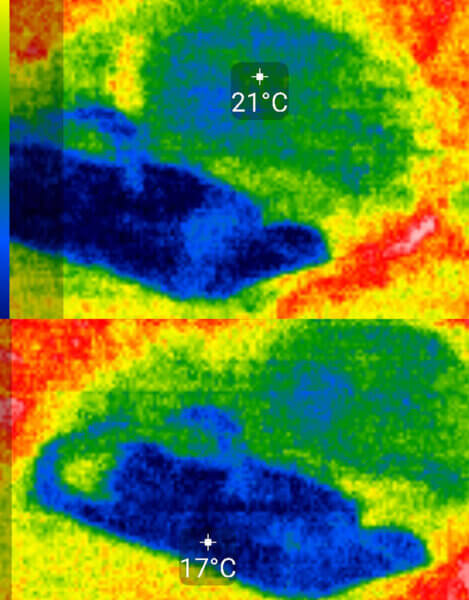

The first thing we noticed when we started looking through the camera was that being in and out of the sun, and what material something is made of, makes a huge difference to heat. A brown table in the sun was 65 degrees, while in the shade some stone was 17 degrees.

The next thing I noticed was that things I didn’t think would make a difference actually made a pretty big difference.

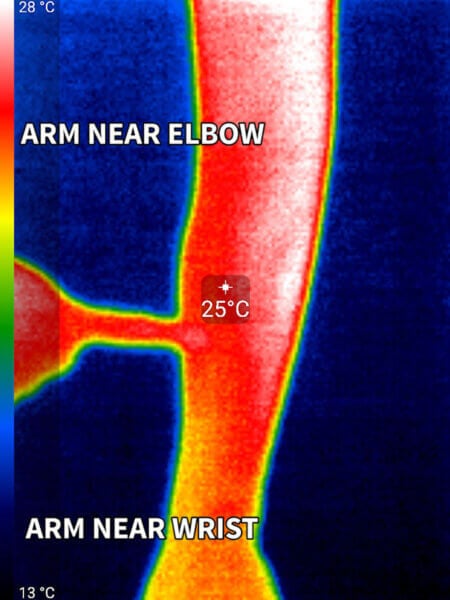

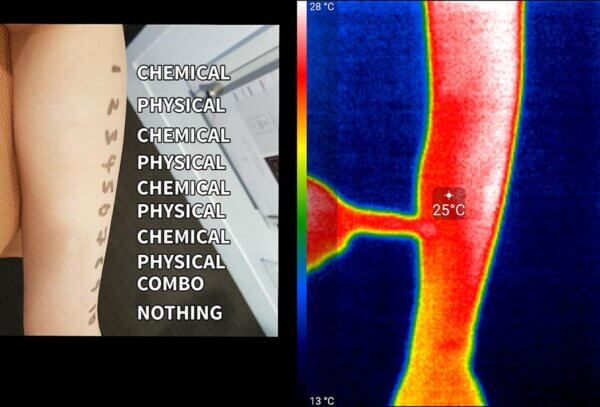

For example, the part of my arm near my elbow was hotter than near my wrist. That’s because things that are closer to the centre of your body are warmer – they’re getting more warmth from things like blood.

(You can see the colour scale on the side – we had it in video mode and wrote down the temperatures, so the number in the middle at any one time might not be relevant.)

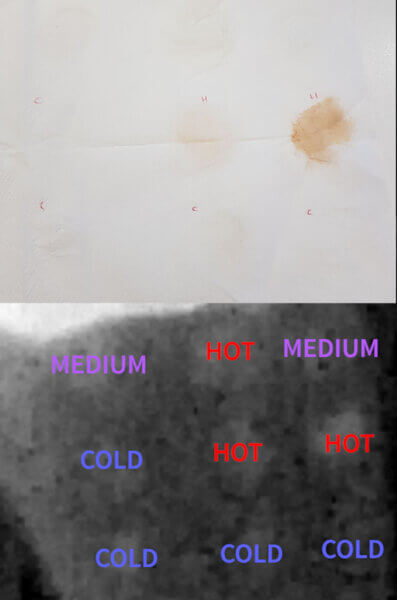

I actually had a whole bunch of sunscreens, both chemical and physical on my arm here, and you can’t see any temperature differences – but you can see the difference between the top of my arm and the bottom of my arm.

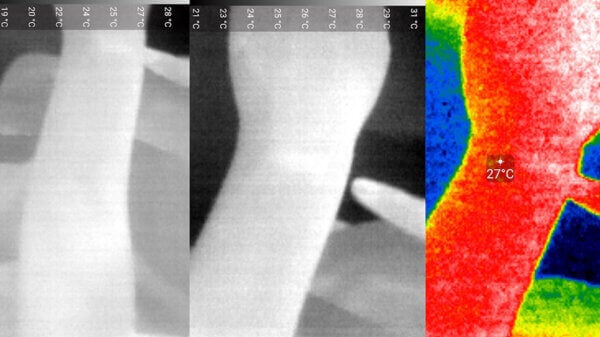

Next I put a thick black marker line on my arm to see if it would make a difference. Black things absorb a lot of visible light from the sun and heat up, so this would be a good test to see what a thin film that converts light to heat really well would look like on the skin. But again, we couldn’t really see much of a temperature difference. I’m pointing to the mark in these photos, and if you squint, you can just see it.

This makes sense when we consider the physics involved. Humans are about two-thirds water. Water is special because it has a really high specific heat capacity – that means it can absorb a lot of heat without itself heating up. So your body is basically a huge heat sink – a very thin film of sunscreen produces a tiny amount of heat that your body’s water can easily absorb without changing temperature.

Sunscreens without skin

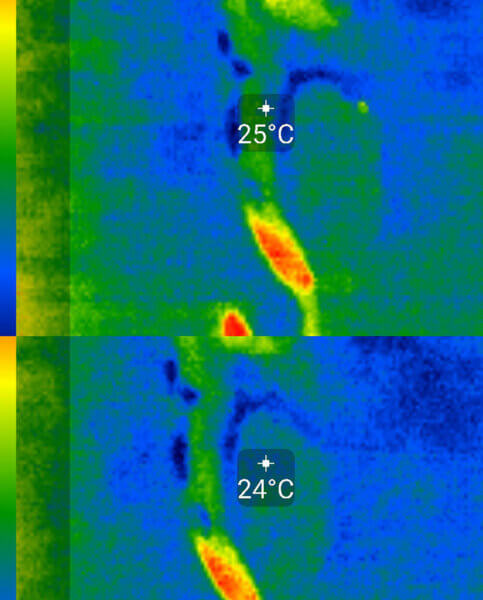

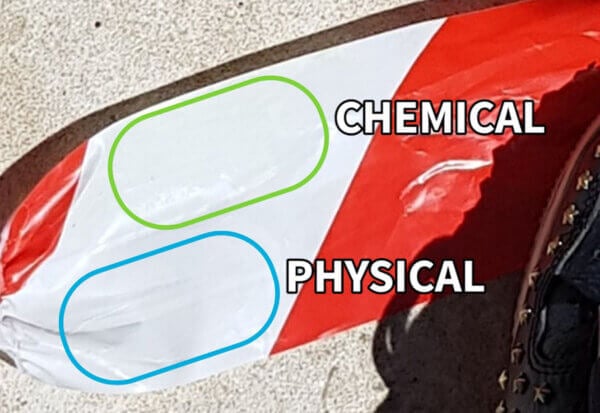

Next we decided to get rid of this heat sink to see if we could see any differences without it. We applied a chemical and a physical sunscreen on a piece of plastic film (well, I applied them while Alex took random photos).

At the start the chemical sunscreen was actually 4 degrees cooler – we figured it was because the sunscreen was still drying, it had ethanol in it that was evaporating, which cooled it down a lot.

We tried again 10 minutes later after everything dried, and the mineral sunscreen was one degree cooler.

But then we turned the film upside down… and the chemical sunscreen was one degree cooler.

So it seems like the angle of the film and the angle of the sun makes a bigger difference than the type of sunscreen.

What about colours?

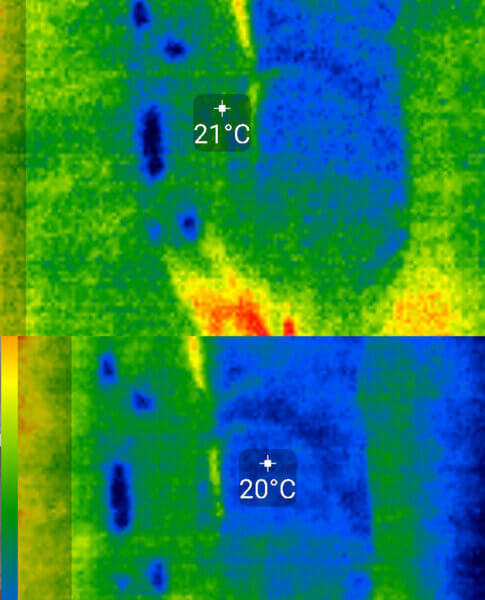

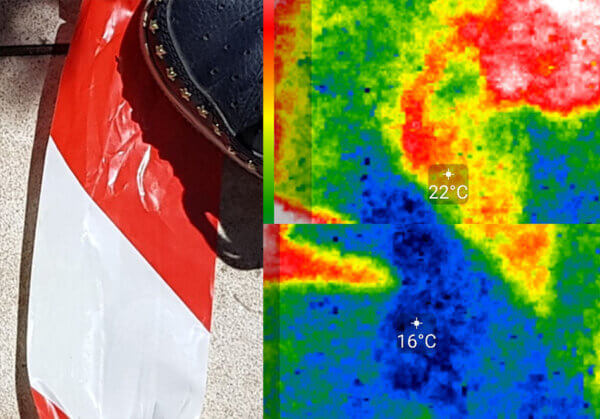

The tape that I liberated from the nearby construction site was red and white, so we decided to just look at that through the camera. The red part of the tape was actually 6 degrees hotter than the white part.

So colours seem to make a bigger difference than whether a sunscreen was chemical or physical.

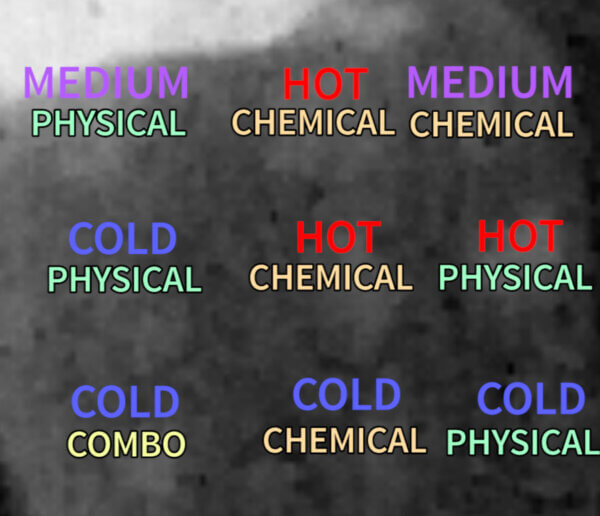

For the final test, I liberated a napkin from a nearby restaurant and blobbed 9 sunscreens onto it. I had chemical, physical, combo, tinted, even one that claimed to have IR protection and cooling effects. We waited 10 minutes for everything to dry, then looked through the camera again.

The first thing we noticed was that the tinted sunscreens were hotter:

With the rest of the sunscreens, there wasn’t really any sort of pattern for which ones were hotter or colder. I was particularly disappointed with the IR protective sunscreen (top right corner) – it would’ve been cool to see that working.

Conclusions

These results make sense, based on the mechanisms of how chemical and physical sunscreens work. There shouldn’t be much heat energy produced at all, and only the tiniest difference between the two types of sunscreen. And given how watery human bodies work, any heat produced shouldn’t be around for very long at all – it dissipates into the rest of your body really quickly.

There’s a lot more visible light in sunlight compared to UV – up to 10 times as much. So it’s not surprising that coloured things (like red tape and tinted sunscreens), which absorb visible light, heat up a lot more. But even then, when it’s on your skin, the heat sink effect happens again and it doesn’t make much of a difference – we couldn’t even see the black marker on my skin. The difference in temperature between the two parts of my arm was much more noticeable.

So, the difference in heat between chemical and physical sunscreens is insignificant. There are other reasons to pick chemical over physical or physical over chemical, depending on your particular situation, but the amount of heat produced shouldn’t factor into it.

(After we did all this, I actually discovered a paper where some physicists calculated how much titanium dioxide nanoparticle sunscreen would heat up skin – they calculated 0.2 °C.)

Thanks to Dr Alex Argyros for his advice on physics things, and helping me out with the IR camera!

References

Krasnikov I, Popov A, Seteikin A, Myllylä R. Influence of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on skin surface temperature at sunlight irradiation. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2(12):3278-3283. doi:10.1364/BOE.2.003278

Hmm, this made me think, although somewhat unrelated: what sunscreens can be taken around in a hot purse all day? Every summer, I store powder sunscreen in my purse for re-application because I figured it was less likely to lose effectiveness than liquid sunscreen if I was out in hot temperatures. Do you know if this the case?

That is really interesting – I always figured it wouldn´t make much of a difference in the grand scheme of things, but it is great to see it inn pictures.

Michelle, I love how you put these things to the test and get them figured out 🙂 Another myth busted! It sounds like of all the variables, the actual sunscreen has a negligible effect on skin temperature and is nothing to worry about.

Hey, this is very informative and helping reading for about heat of sun screens. I rally like this reading. thank you for sharing it.

Thanks Michelle love reading your reviews.