There’s tons of misinformation on the dangers of sunscreen on social media, and it seems like all of the myths make the rounds each time a new platform emerges. Currently the trending platform is TikTok.

Even though sunscreen safety is a topic I’ve covered many times, it repeatedly comes up in many different flavours.

I’ll break down the misinformation in two videos that went viral – one on some common myths about mineral and chemical sunscreens, and the second on some more technical aspects that is largely just sciencewashing.

The full video version is here, keep scrolling for the text version…

Mineral vs chemical sunscreens

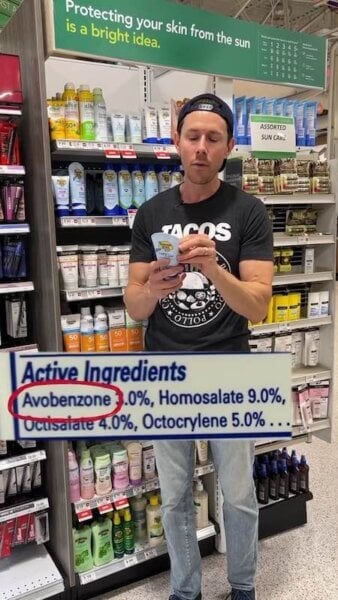

Last time I debunked a video from Bobby Parrish who goes by FlavCity. He also filmed a video on sunscreens:

Bobby: “The cosmetics industry is not regulated nearly as much as the food industry. Which is really scary, because this stuff goes on your body.

So, the question is, what’s the best sunscreen as the summer comes upon us?”

Risks of skin versus food

First off, stuff that goes on your body is generally less scary than stuff that goes in your body. Skin’s main function is to act as a barrier.

Related post: The “60% of products absorb into your bloodstream” myth

Sunscreen falls under drug regulation

Additionally, sunscreen is a drug in the US (where he is), not a cosmetic. So he’s talking about entirely the wrong category here.

Minerals and skin penetration

As you’d expect, he recommends mineral sunscreens over chemical ones.

Bobby: “Well, there’s two kinds of sunscreen. There’s a mineral-based, the good ones, and chemical-based, the bad ones.

Minerals are often made of zinc oxide, and that’s good because it never penetrates your skin. The chemical-based ones are made with chemicals that penetrate your skin and can be found in your body, in your breast tissue, in baby milk, breast milk, up to three or four weeks later.”

First off, minerals can penetrate your skin, especially if they have small enough particles. That’s actually why a lot of places have a different safety assessment specifically for nanoparticles.

I feel like I could just post myself saying this on social media every week, but the amount with normal use doesn’t seem to be a significant health risk.

That’s the fundamental reasoning for any recommended amount of ingredients in cosmetics, and it’s pretty much the same situation for chemical sunscreens – although obviously there’ll be different percentages set for different substances.

Chemical sunscreens penetrate skin?

There’s a huge diversity of properties within chemical sunscreens – a lot of the newer chemical ingredients were specifically designed to not get through skin easily.

There were these studies on sunscreens done by the FDA a while ago, which were widely publicized as “Sunscreens get all the way into your blood.”

Related post: Sunscreens in your blood??! That FDA study

This wasn’t a new discovery, but one handy aspect of the FDA studies is that they measured the blood concentrations.

If you do a bunch of rough calculations, you’ll see that only a fraction of a percent of most of these chemical sunscreens get absorbed.

Related post: More Sunscreens in Your Blood??! The New FDA Study

Also if you’re wondering, the safety assessments do take into account developing fetuses. Usually, that’s the endpoint that they’re based on – I went through the safety assessment of oxybenzone as an example.

Related post: US Sunscreens Aren’t Safe in the EU? The Science

Good vs bad ingredients is a myth

This whole good ingredient versus bad ingredient thing really makes me cringe, because it is such a big red flag. Good and bad depends entirely on dose and exposure.

Even a seemingly benign substance can be dangerous at a high dose (e.g. water poisoning, oxidative damage from oxygen), and conversely, a seemingly dangerous substance can have minimal health impact at a small dose (e.g. we naturally have uranium and formaldehyde in our bodies).

Zinc oxide is not completely safe

Zinc oxide does have tons of downsides as a sunscreen ingredient, which I’ve talked about before.

The main one is that it is not very good as a sunscreen. You need lots of it to absorb a relatively small amount of UV.

People also underapply it because it’s got a white cast and it usually has a thick, sticky texture.

Related post: Zinc Sunscreens Don’t Work Better: Every Myth Busted

It’s also not that great for the environment, despite what everyone seems to be assuming (a topic for a later video).

Spray sunscreens

Bobby: “When you pick up a chemical-based one, you’re always going to see the same active ingredients: avobenzone, homosalate, octisalate.

These are the kind of chemicals you want to avoid, and if you’re ever thinking about using any kind of spray, spray bottle like this, avoid it, because when it goes into the air, it can be inhaled into your lungs and coat the inside of your body.

If you want to see a video about the best mineral-based sunscreens, let me know, and I’ll make a part two of the video.”

It’s extremely weird how Bobby says inhaling a sunscreen will cause them to “coat the inside of your body” – like your body is just hollow and you don’t have other stuff inside your body.

I personally don’t really like spray sunscreens because there are a lot of downsides. Anatomical accuracy aside, the reference he made to inhalation risk it is actually a good point.

The health risk from inhaling sunscreen is generally quite low, and is taken into account in the safety assessments.

However, the risk is generally considered higher for mineral sunscreen ingredients. But with any sort of spray sunscreen, I think it’s still not a very nice experience to inhale sunscreen. And you do end up with lower protection, because your insides (and everything else the spray covers) do not need protection from the sun.

Hormone disruption from chemical sunscreens

The second video comes from a pharmacist-turned-hormone consultant (?), It’s a bit harder to see through this because there’s a bit of technical jargon involved, but I’m quite familiar with the background since my PhD was in medicinal chemistry and I studied pharmacology as part of my undergraduate degree.

@HormoneSpecialist: “Our next estrogenic is sunscreens.

I don’t know of any sunscreen with a chemical UV filter in it that doesn’t have some affinity for hormonal receptors in the human body. Some of the common ones are benzophenone-3 (BP3), benzylidine camphor-3 (BC), 4-methylbenzylidine camphor (4-MBC), but there are dozens of them.

Watch out for the root benz or phen in the chemical name. Better yet, just don’t use a chemical-based sunscreen.”

Affinity doesn’t translate to an effect

First off, “affinity” refers to how strongly something binds to a receptor. “Some affinity” simply means a sunscreen molecule can stick to a hormone receptor inside your body.

It’s probably true that chemical sunscreens all have some affinity for some hormone receptors, and it’s not that surprising – lots of substances will bind to receptors in our bodies.

But “some affinity” doesn’t tell us much about the risk of bad health effects. Things that bind to the same receptor can have completely opposite effects (known as agonists and inverse agonists), or even no effect (antagonists):

One common example is with opioid receptors, which is where opioids like fentanyl and heroin act. Both have affinity for the receptor (they will stick to it), but they also have efficacy (they will actually trigger an effect there).

On the other hand, there’s Narcan (naloxone) which is used to treat opioid overdoses. The way it works is also by binding to the same receptors, and it actually has more affinity (it sticks more strongly). However, it doesn’t actually trigger an effect (really low or no efficacy). It essentially kicks out heroin or fentanyl or whatever the person is overdosing on. So despite higher affinity, its lower efficacy means it’s safer.

A common analogy is a key and a lock. Both heroin and fentanyl are keys that can open this particular lock, but naloxone is like a sticky key that fits in the lock but doesn’t open it. It actually gets stuck there and blocks keys that will open the lock.

Affinity is still dependent on exposure

On top of that, binding affinity refers to what happens when the sunscreen molecules and the receptor actually meet. But the sunscreen has to get to the receptor in a high enough concentration first. And where that receptor is in your body can mean that binding there will trigger different effects.

So, this all sounds scary because it’s unfamiliar and technical, it doesn’t really mean much. Sunscreens still need to be assessed for safety on a case-by-case basis, which is actually what happens for sunscreens to get approved – whether chemical or physical.

Lipophilic substances absorb easily?

@HormoneSpecialist: “Chemical sunscreens are lipophilic, meaning they’re attracted to fat, and we all have a fatty layer in our skin, so a lot of it absorbs right in. It doesn’t just stay on the surface.

Remember, the skin’s an effective dosing route for hormones and drugs applied as creams. So, yes, it acts as a barrier and protection from exposures to lots of different things. But to substances with the right properties, your skin is like a wide open, unguarded back door.

And what goes in through the skin dumps right into the bloodstream without being metabolized at all by the liver, like food and other things we eat which go to the liver first and then into circulation. It’s like getting these chemicals by injection. Yikes!”

Here’s another series of arguments that doesn’t quite make scientific sense. But they’re based on a grain of truth, and they sound complicated and scary enough that people aren’t going to question him. So, let’s break it down.

First off, most chemical sunscreens are indeed lipophilic, which means they’re oil-loving. But contrary to his claim, substances that are too lipophilic don’t get through skin easily.

His description makes it sound like the fatty layer under the dermis (hypodermis) is like a magnet that sucks lipophilic substances like chemical sunscreens through the skin.

But lipophilic things stick to fat or oil through attractions called dispersion forces, and these are really short-range. They don’t act like a magnet, and can’t suck things through the skin. Essentially, the chemical sunscreen has to bump into the fat or oil before it sticks.

Most people will know through personal experience that body oil, greasy sunscreens or even skin sebum don’t just get sucked through skin. You can’t feed yourself by rubbing coconut oil on your skin.

Some things do absorb easily… but not chemical sunscreens

He is correct in saying that some substances can get through skin really easily if they have the right properties – but this set of substances is quite small, and doesn’t include chemical sunscreens.

There are a lot of medications that need to be distributed through the bloodstream, but very few of them are delivered as creams. If injections and creams did the same thing, we would never inject things – injections are far more annoying and painful.

Substances that go through skin easily have to have the right balance of lipophilic and hydrophilic. Skin has a complex structure with some oily layers and some watery layers, and a substance will need to pass through these layers into the dermis to get to the bloodstream.

For example, the top layer (the stratum corneum) is pretty oily, with oily “mortar” between dead skin cell “bricks”, while the lower layers with living cells tend to be more watery.

So if a particular chemical is too lipophilic or too hydrophilic, it gets stuck on its way to the bloodstream. Chemical sunscreens are quite lipophilic, so most of them actually get stuck in the stratum corneum. That’s actually how chemical sunscreens sink in a bit and last for longer than physical sunscreens.

There is data on how much chemical sunscreens absorb into the blood – for most of these, it’s a fraction of a percent that makes it through.

Related post: More Sunscreens in Your Blood??! The New FDA Study

Working out how much of a chemical is likely to absorb into the blood is part of the toxicological assessment that’s done for sunscreens. I’ve discussed it before in my post on EU safety assessments of sunscreens, and he doesn’t seem to be aware of the newly released SCCS assessments for benzophenone-3 (oxybenzone) and 4-MBC.

The EU were only reassessing potential endocrine disruptors, and only a few chemical sunscreens had enough evidence to be worth reassessing. Of those, there wasn’t enough evidence to say any of them are endocrine disruptors, except perhaps 4-MBC.

Related post: US Sunscreens Aren’t Safe in the EU? The Science

The reason that they’ve ended up at a different conclusion from him is because he’s just taking studies at face value. He’s assuming what happens in the study is exactly the same as what happens when we apply sunscreen on our skin – a common issue with fearmongering sources like the EWG.

But studies in the literature generally aren’t done under realistic conditions. Many are animal and cell line studies, which obviously needs to be translated to application on human skin. And even with human studies, the conditions used are usually really artificial, like using way more sunscreen than any regular person would.

In proper safety assessments, studies are interpreted and translated to make their results actually relevant to how consumers use sunscreens. These assessments are the basis of the usage guidelines that formulators follow when they’re making sunscreens. Both “sides” are using the same evidence, but toxicologists are interpreting the studies in a nuanced and scientific way, whereas a lot of people just aren’t doing any interpretation.

Sunscreens add up?

@HormoneSpecialist: “You may say, ‘Well, I don’t often use sunscreen, so this really isn’t an issue for me.’ But remember, it’s in cosmetics too, like makeup, skin creams, and even some soaps. So daily application is a likelihood for a lot of people.

Now, chemical UV filters are required to be listed as an ingredient in cosmetic products, but protecting human skin is not their only use. They also protect other materials from the harmful effects of UV light, like plastics, carpet, furniture, and all of this is taken into account in toxicological assessments.”

I’ve discussed this in part 1 of this series in the context of propylparaben exposure, as well as in the breakdown of the EU sunscreen safety assessments. It really drives me up the wall when people say, “but it adds up,” like it’s some sort of huge revelation.

It is not a huge revelation. It is really obvious. Everyone from the age of maybe 20 onwards (I’m being generous here) knows that people commonly use more than one product. Toxicologists assess usage every day as part of their jobs – they have thought of this.

You might also enjoy Part 1 on propylparaben and Part 2 on a whole bunch of other ingredients including fragrance, colorants and talc. The video version also includes a long rant on the state of misinformation and how to be a better consumer at the end.

Lots of people want to make money sitting on their bum in front of a camera. To do this you need “content”. Content that is associated with sex or fear or death etc gets a lot of hits. This is how to make money on social media. There are only a handful of YT content providers I bother to look at and Lab Muffin is one of them.

Thank you! I do sometimes think about how much money I could make if I didn’t have a conscience 🥲

Thank you for your informed, knowledgeable and straightforward information on all things skin and cosmetics. I have been in the industry for over 25 years and am so grateful to you for setting the record straight and illuminating a field that desperately needs true scientific clarity. Please keep up the phenomenal work you’re doing!!

Thank you!

You are truly amazing! Thank you for providing us with this information. I have a question that I’ve been trying to figure out for a while now, I can’t find anything about it online and the only person I could think of who might know the answer was you. Can for example x-rays and metal detectors used in airport checks affect sunscreens in any way? I usually take quite a few bottles with me when I travel. This thought brought up another question, can keeping the sunscreen

near a cellphone affect sunscreen? (I’m thinking of the radio waves). For example having them both in the same pocket or bag, or just close. I really apologize for the long questions but these thoughts really haven’t been able to leave my head

Radio waves should be fine, since they’re very low energy. I’m not 100% sure about x-rays, but I don’t think they should be a huge issue – the amount of x-rays used these days for carry-on baggage is too low to even register on photographic film, the amount used for checked baggage is higher but still very low, and I would expect some of these processes would be used for commercial imports as well.

Hi Michelle,

Thank you so much this was a great breakdown! I wonder if you have any information on how to assess/verify the quality of individual sunscreen products (or brands as a whole)? I was just reading the Consumer Reports assessments on sunscreen products, and it looks like a lot (all?) of them don’t live up to the SFP they are labeled as, and I’m not sure what to make of that. Are there standards for ingredients/percent concentrations to look for? Or other sources where the efficacy of products are published?