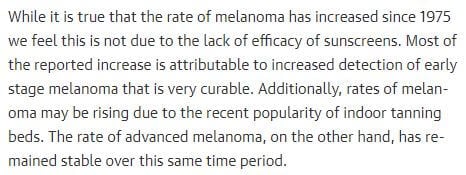

There’s been a recent study published about the sunscreen ingredient octocrylene turning into benzophenone over time. According to the paper, “benzophenone is a mutagen, carcinogen, and endocrine disruptor”.

I wasn’t going to do a proper analysis of this paper because it only really got lots of attention in France and not many other places, but then I saw that I was cited in it.

Twice.

As “propaganda”.

So here’s my analysis – the video version is here on YouTube, keep scrolling for the written version (with 500% less Taylor Swift memes and dramatic readings).

So this paper: “Benzophenone accumulates over time from the degradation of octocrylene in commercial sunscreen products.” It’s… a bit weird. (It’s open access – you can read it here.)

What did the researchers do?

Let’s start by looking at what the researchers actually did. In a science paper this is in the methods and results sections, and this part is pretty standard.

Octocrylene is a pretty common sunscreen ingredient. Under certain conditions, it can turn into another chemical called benzophenone which the paper paints out to be really, really nasty (more on that later).

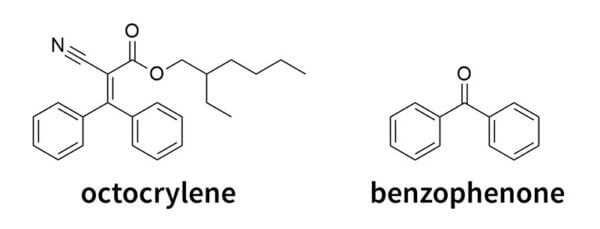

The researchers bought 17 different sunscreens (3 bottles of each), with 16 of these containing octocrylene.

- They measured the benzophenone concentrations in them right after buying them.

- Then they kept them for 6 weeks at 40 °C (in stability testing, this approximates one year of normal storage), then measured the benzophenone levels again.

- Initially there was benzophenone in all of the octocrylene sunscreens (average 39 ppm). There was barely any in the one without octocrylene.

- After the 6 week storage, benzophenone increased in all of the octocrylene sunscreens by 14.5-199.4%, to an average of 75 ppm, with the highest measured concentration being 435 ppm.

There are some limitations with this study. The most obvious one is that 6 weeks at 40 °C isn’t quite the same as one year of normal storage – some reactions that go at 40 °C that wouldn’t normally go at room temperature. But based on these results, it’s probably safe to say that some octocrylene in sunscreens will turn into benzophenone over time.

Is this actually a problem? Well… this is the controversial part of this paper – the interpretation of what this result means, how the paper tries to put it into context. This is in the introduction and discussion parts of the paper.

How bad is benzophenone?

If you just read the paper, then it seems like the science is pretty clear: benzophenone is really dangerous.

The start of the abstract: “Benzophenone is a mutagen, carcinogen and endocrine disruptor.”

In the intro, there’s four chunky paragraphs on how bad benzophenone is.

“Benzophenone is associated with a wide range of toxicities including genotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and endocrine disruption.”

“Benzophenone is an established carcinogen.”

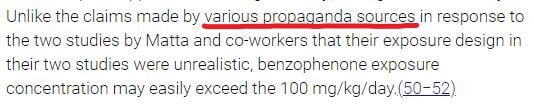

The problem is: the evidence that the authors cite to show this is mostly in vitro assays, and studies in cells, mice, guinea pigs, rats and zebrafish (references – things we’re not. This isn’t the scientific consensus in humans at all.

The authors cite a few reviews on the risks of benzophenone in humans in this paper. These analysed the same in vitro and animal studies that the authors looked at, and they came to very different conclusions.

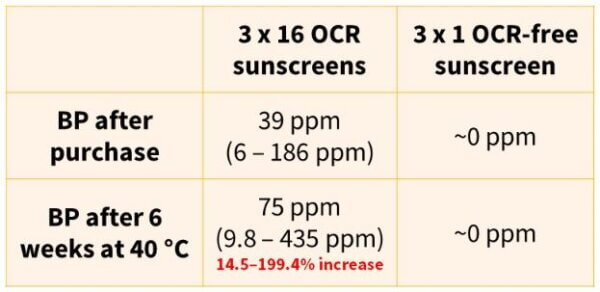

The International Agency on Research in Cancer report concludes that there’s no data in humans, and there’s no solid explanation for how benzophenone could cause cancer in humans. But because it happened in animals, they can’t say whether or not it would also happen in humans. So they basically went *dunno noise* and put benzophenone in Group 2B: Possibly Carcinogenic to Humans.

This sounds pretty bad, but it means that it missed out on:

- Group 1: Carcinogenic to Humans

- Group 2A: Probably Carcinogenic to Humans

Other things in Group 2B include lead, progestogen-only contraceptives, mobile phone radiation and aloe vera extract. It’s a mixed bag. It’s not exactly as strong as stance as you’d think from reading the statements in this paper.

The authors also cite the European Food Safety Authority’s 2017 safety assessment. As you probably guessed they were looking at eating benzophenone, a route of exposure that’s usually considered worse than just putting it on your skin.

Their conclusions:

“there is no concern with respect to genotoxicity… The Panel concludes that there is no safety concern for benzophenone under the current condition of use as a flavoring substance.”

Which again, doesn’t really match what the authors of this study are saying.

But it does explain the fact that benzophenone isn’t on that EU list of banned ingredients and cosmetics that clean beauty people like to point to.

And it also explains the fact that safety assessors already know there’s benzophenone in sunscreens, and they’re okay with it. Benzophenone is a known contaminant in the octocrylene that gets put into sunscreens. It’s actually listed on the safety data sheets from ingredient suppliers (they’ve included an example in the supplementary info of this paper). That means that toxicologists do actually consider the benzophenone that you rub onto your skin when they’re doing safety assessments for octocrylene sunscreens.

Octocrylene is used at a maximum of 10% in sunscreens. The highest amount measured in the study is a fair bit higher than 10% of the known benzophenone contamination from popular octocrylene suppliers (~200 ppm). But the FEBEA (French federation of beauty enterprises) points out that even with daily application of 18 g of the highest benzophenone sunscreen from this study, you still end up with less than 0.5 mg benzophenone. This is three times less than the maximum allowed dose if you’re eating it.

So how do the authors explain why their conclusions are so different from the scientific consensus? Well… they kind of just say that the other people are wrong.

“…the risks have been underestimated in both toxicology journal papers and organisational reports. This is unfortunate…”

Not only that, but the authors say that these other people “can be argued to be unjustified and irresponsibly reckless“.

So all of these EU scientists who specialise in human toxicology (you can check out their CVs and detailed conflicts of interest declarations on the EFSA website – the EU doesn’t mess around when it comes to regulation) –

– they’re all wrong, but the authors are right?

Let’s look at the authors.

There are five authors. Four of them are from an ocean research institution. One of them is a human toxicologist, but he’s retired, and he’s not affiliated with any research institutions.

Hmmm.

But their actual qualifications don’t always matter! Maybe they have good evidence? Maybe they reference other authoritative sources that are as qualified and reputable as the IARC and the EFSA, and maybe they say that the body of evidence shows that benzophenone is really dangerous to humans?

No, none of their references say this.

What other evidence do they have?

The evidence that the authors cite, apart from all the in vitro and animal studies that experts with much more expertise have interpreted completely differently:

A court case – lawyers aren’t exactly qualified in toxicology, so that doesn’t mean much

And supposedly, Proposition 65.

Proposition 65

The authors say: “under the State of California Proposition 65 there is no safe harbor or allowable level of benzophenone contamination in a product“, and that this reflects the dangers of benzophenone. They cite a list of safe harbour numbers that doesn’t mention benzophenone.

This makes it sound like California thinks that benzophenone is so bad that no amount should be allowed, but… that’s not how it works.

Proposition 65 is a law that makes companies put up warning signs about potential toxic chemicals. You might know it from the “coffee, potato chips and Disneyland give you cancer” signs that went viral a while back.

Firstly, this regulation obviously results in a lot of warning signs that don’t really mean much in reality. This is because it takes a hazard-based approach, which is what I talked about in my clean beauty post (clean beauty does the same thing). If something has a potentially dangerous substance in it, then it gets a Proposition 65 warning. It doesn’t matter what dose you get, and how you get it – whether you inhale it, or eat it, or put it on your skin.

These different exposures are pretty darn fundamental when it comes to toxicology. Obviously, injecting a liter of something versus putting half a drop on your skin are going to have very different effects.

But that aside, more importantly: “no safe harbour” in Proposition 65 doesn’t mean it’s so bad that no level is allowed. It actually means that they just haven’t decided on a safe level yet.

From the Proposition 65 website:

To guide businesses in determining whether a warning is necessary or whether discharges of a chemical into drinking water sources are prohibited, OEHHA has developed safe harbor levels for many Proposition 65 chemicals. A safe harbor level identifies a level of exposure to a listed chemical that does not require a Proposition 65 warning. A business does not need to provide a warning if exposure to a chemical occurs at or below these levels. These safe harbor levels consist of No Significant Risk Levels for chemicals listed as causing cancer and Maximum Allowable Dose Levels for chemicals listed as causing birth defects or other reproductive harm. OEHHA has established more than 300 safe harbor levels and continues to develop more levels for listed chemicals.

There are lots of chemicals that don’t have a level, and they’re slowly being added to Proposition 65. And this makes more sense, because if benzophenone was so bad it’s never allowed, then grapes would be illegal in California (grapes are a natural source of benzophenone).

70% absorption?

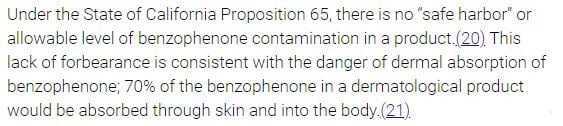

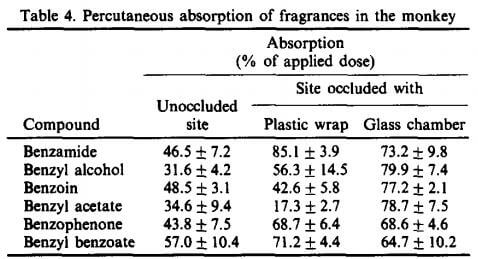

In the same paragraph, the authors also say that 70% of benzophenone that you put on your skin gets absorbed through skin. But if you look at the study they cite, it’s 70% absorption under occlusion – in other words, 70% absorbs if you wrap it in cling wrap after you apply it.

Occlusion increases absorption, and that’s not how we wear sunscreen. The cited study does an uncovered absorption as well , and it’s a less scary-sounding 44%. These numbers are right next to each other in the table in the study:

So for some reason, the authors quoted the less relevant number. (Also it was done in monkeys.)

So to me, there seems to be a sort of pattern in how the authors are selecting and presenting the evidence about benzophenone.

Now, the authors don’t just disagree with the scientific consensus about benzophenone toxicology – they also disagree with dermatologists about sunscreen:

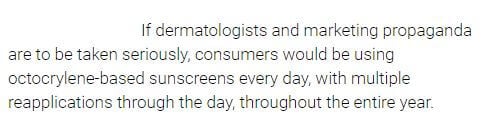

The authors imply that “dermatologists and marketing propaganda” shouldn’t be “taken seriously” when they recommend wearing sunscreen regularly throughout the year, and reapplying sunscreen:

I don’t think I have to point this out, but that is the medical consensus from all of these organisations (very much not an exhaustive list):

- American Academy of Dermatology

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- World Health Organisation

- Skin Cancer Foundation

- Cancer Council Australia, the Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society, Osteoporosis Australia, Australasian College of Dermatologists

- Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency (ARPANSA)

And then, joining the ranks of people that the authors disagree with, there’s me. Apparently I’m part of “various propaganda sources”.

And while I’m really flattered to be cited (not just once, but twice!), it’s also really bizarre. (Although maybe not that bizarre in the context of this paper.)

I’m a blogger and YouTuber. I’m not a huge media outlet, and I’m not an academic. I mean, this is me:

And the two blog posts that got cited were actually some of the least propaganda-y of my posts. They were the ones where I talked about the FDA studies. The media reported this as:

I pointed out that this study didn’t mean we should to freak out and change sunscreens. My sneaky propaganda tactics were:

- Quoting actual lines from the study

- Quoting the FDA, who did the study

- Quoting the editors of the journal that published the study

- Quoting experts and the American Academy of Dermatology

I guess maybe the authors think that we’re all propaganda and we should be listening to the media headlines instead?

So why did a bunch of scientists come out with a paper that makes so many unusual claims? I mean, I’ve read a lot of peer-reviewed papers, but disputing the scientific consensus of cancer organisations and toxicologists and dermatologists without much evidence, and citing a beauty blogger – it’s really just A LOT in the one paper.

Well, I think looking at what else the authors have done gives a bit of insight here.

Like I said, four of them are from an ocean research institute and one of them used to be a human toxicologist. I think the obvious question is – why didn’t they collaborate with an academic who currently works in human toxicology?

The only author who specialises in human toxicology on this paper that talks a lot about human toxicology is someone who, firstly, isn’t affiliated with an academic institution, but also he’s retired and he doesn’t have a PhD. It’s weird. I know this sounds elitist, but that’s just how scientific academia works – the first step in your training is getting a PhD.

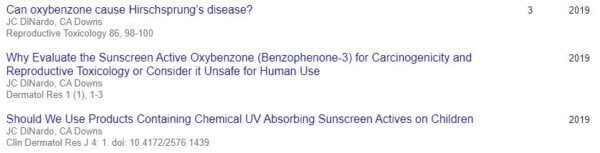

And it’s not a one-off either. It’s a bit of a pattern in the publication history of the first two authors, Craig Downs and Joseph DiNardo.

Craig Downs is the scientist who published and promoted the coral studies that led to the whole reef-safe sunscreen thing in 2018. He’s been very active in getting particular chemical sunscreens banned in places like Hawaii. Since then he’s published more studies on how sunscreen impacts aquatic organisms (which is what you’d expect from a marine biologist), but he’s also started collaborating with Joseph DiNardo on papers about human toxicology:

The only link between these papers and his older work is that they’re all about how bad chemical sunscreen is, in all sorts of different ways. Which is weird. Scientists usually have expertise in a specific field, and specialise in particular methodologies. They don’t jump around different fields focusing on a specific group of chemicals.

This publication history doesn’t make a lot of sense in my opinion. But if you look at some of the other things that Downs and DiNardo have said outside of their peer reviewed publications, then you can sort of see that all roads seem to lead back to chemical sunscreens.

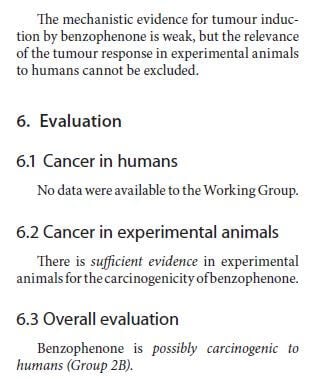

Increasing melanoma rates?

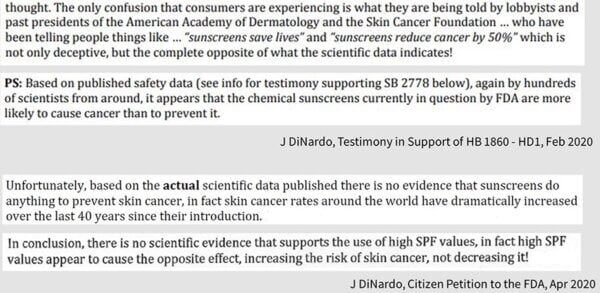

It’s because of too much sunscreen. According to DiNardo’s FDA submissions, the “actual scientific data” shows that sunscreens are “more likely to cause cancer than to prevent it”, and the American Academy of Dermatology and the Skin Cancer Foundation are misleading consumers.

Again, I don’t think I need to point out that experts have the opposite opinion: that sunscreen can reduce skin cancer, and increasing melanoma rates are because of better detection and different lifestyle habits. Apparently they’re wrong.

Declining coral reefs?

According to Craig Downs, it’s his “professional opinion that most of the coral reefs in the last 40 years have died because of your bathroom than anything else: climate change, oil spills, what have you.”

This is not what most coral scientists think. The consensus is that the biggest threats to coral are climate change, ecosystem changes (e.g. overfishing), and land-based pollution from industrial sources like agriculture.

Related post: More SPF Mythbusting (with video)

A recent open access review looked at all the studies on sunscreen and coral. The measurements that Downs took around Hawaii were ten to a thousand times higher than any other published measurements.

The conclusion is: “organic UV filters do occur in the environment but according to our analysis there is limited evidence to suggest that their presence is causing significant harm to coral reefs“, although more research should be done.

As you might have expected, DiNardo has said that their lead author was hired by Big Sunscreen.

Now I think there are lots of legitimate criticisms of the beauty and personal care industry, and we can’t just trust everything they say. I talk about marketing myths all the time. But that doesn’t mean that the complete opposite of what the industry says is always going to be true.

And what are the chances that everyone in the industry, and in toxicology, dermatology and coral science are all in on the same conspiracy to protect Big Sunscreen? People like to blab. In a decades-old conspiracy, there’s going to be thousands of people involved. How has no one leaked receipts about all their secret meetings and how people are getting paid off?

I think, if you have to dispute the scientific consensus in multiple fields to support your theory, including fields that you don’t have expertise in, and you don’t have strong evidence that other people haven’t seen before to support your theory… then maybe it’s time to ask yourself if perhaps you’re being a bit biased.

Why did the French (and only the French) care so much?

What about the other three authors?

I mentioned this before – one of the weirdest things about this paper is where it took off. It’s a paper in English, and the authors are from the US and France.

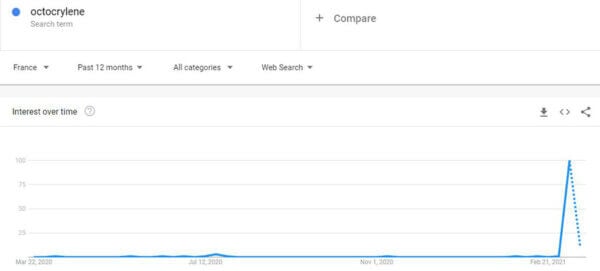

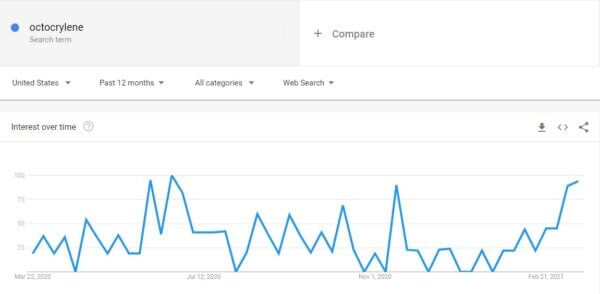

In France, the paper got tons of attention almost immediately after it was published, with lots of media coverage. But in the US, there was barely a blip. You can see this in these Google Trends graphs:

This discrepancy is really weird. Skincare people talk about sunscreen all the time. But for everyone else, and the media in general, interest in sunscreen is cyclical. There are exceptions, but it’s pretty rare for people to care this much about a small study – especially in a country where people mostly just wear sunscreen to the beach, if at all. So what’s going on?

Here’s one suggestion I’ve seen from French bloggers and beauty experts. If you look at the conflicts of interest section of the paper, the ocean research institute that four of the authors work at has partnerships with Pierre Fabre, a huge French cosmetic and pharmaceutical company.

A few days after this paper was published, Pierre Fabre announced that they were launching a sunscreen with a new filter called Triasorb, and “octocrylene-free” features heavily in their marketing.

Laurence Coiffard, professor of cosmetology at the University of Nantes, has doubts about the objectivity of this research, “the team which carried out this research was funded by the Pierre Fabre laboratories, at the same time the Pierre laboratories Fabre are launching marketing around their products without octocrylene.” (machine translation from French)

The timing and the hype that was almost entirely isolated to one country does seem a bit suspicious, but Pierre Fabre have denied any involvement.

I don’t think that a conflict of interest means the science will automatically be compromised. It’s unfortunate, but science is expensive, and a lot of topics just aren’t that high up on the priority list for the government to fund them without commercial interest. But it’s a bit of a strange juxtaposition, with all this stuff in the paper about marketing propaganda and Big Sunscreen.

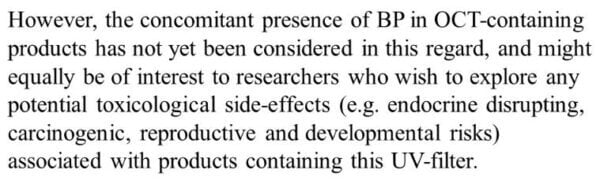

Another study came out from a Belgian research group at the end of March, and they also found that benzophenone increased after octocrylene sunscreens were kept at high temperatures. So again, I don’t think the experiment part of this study was wrong. But if you compare the two papers, you can see how differently the two papers contextualise their findings. The other paper mentions that benzophenone is a potential endocrine disruptor and carcinogen but clearly frames them as “potential”:

There are some other things I haven’t mentioned that to me also seem like pretty big red flags:

- DiNardo’s public email address for a while was [email protected].

- Downs’ lab runs a program that’s a lot like the “EWG-approved” label, where they’ll certify that your sunscreens are reef-safe with their own unofficial procedure (for a fee).

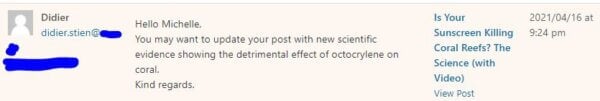

- Late addition: Didier Stien, one of the authors from the Pierre Fabre-affiliated lab, commented on my blog post about sunscreens and coral reefs in mid-April, suggesting I add information on octocrylene being bad (he conducted some of these studies, and they were reviewed in the Mitchelmore review). I’m not sure why he’s reaching out to someone he called a “propaganda source” – it seems kinda sus.

Takeaways

The takeaways from this:

With octocrylene and benzophenone: the vast majority of scientists don’t think that benzophenone is as bad as the paper makes it out to be. But the amount can get higher than expected, although it is still within the margin of safety for oral exposure).

Hopefully there’ll be a bit more research on how benzophenone affects humans when we put it on our skin, and sunscreen formulators will focus on ways of stabilising octocrylene. In the meantime, as many skincare experts have said, it’s probably still safe to use octocrylene sunscreens as long as you’re not allergic to them. But it’s safest to not use sunscreens after their use-by date, and not expose them to high temperatures for long periods (which are things you were hopefully doing anyway).

The wider takeaway is: you can’t trust everything you read just because it’s in a peer-reviewed paper.

This paper had five authors who all apparently signed off on it, and there were four anonymous reviewers as well. Things slip through peer review all the time, especially when it’s commentary around the relevance of the research, since that part isn’t checked anywhere near as thoroughly as the actual experimental part.

References

Downs CA, DiNardo JC, Stien D, Rodrigues AMS, Lebaron P, Benzophenone accumulates over time from the degradation of octocrylene in commercial sunscreen products (open access), Chem Res Toxicol 2021, 34, 1046-1054. DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00461

EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes, Flavourings and Processing Aids (CEF), Silano V, Bolognesi C, et al., Safety of benzophenone to be used as flavouring (open access), EFSA J 2017, 15, e05013. DOI: 10.2903/j.efsa.2017.5013

IARC, Benzophenone in IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 2013, 101, 285–304.

Octocrylene in sunscreen products degrades into benzophenone, study, Premium Beauty News, 11 March 2021 (last accessed 26 April 2021).

DiNardo J, Citizen Petition to the FDA, 17 April 2020.

DiNardo J, Testimony in Support of HB 1860 – HD1, February 2020.

Rubin CB, Brod B, Comments on Natural does not mean safe – the dirt on clean beauty products, JAMA Dermatol 2019. DOI: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2724.

Downs C, Talk at Ban Toxic Sunscreens Hawaii, June 2017.

Bronaugh RL, Wester RC, Bucks D, Maibach HI, Sarason R, In vivo percutaneous absorption of fragrance ingredients in rhesus monkeys and humans, Food Chem Toxicol. 1990, 28, 369-373. DOI: 10.1016/0278-6915(90)90111-y

Mitchelmore CL, Burns EE, Conway A, Heyes A, Davies IA, A critical review of organic ultraviolet filter exposure, hazard, and risk to corals (open access), Environ Toxicol Chem 2021, 40, 967-988. DOI: 10.1002/etc.4948

Gorospe K & Humphries A, To lather or not to lather? Providence Journal, 27 Jun 2018 (accessed 29 July 2018).

Gregory K, Hawaii bans sunscreens with chemicals that damage coral reefs, but Australia reluctant to follow, ABC News, 4 May 2018 (accessed 29 July 2018).

Mitchelmore C & Fenner D, Opinion: Data doesn’t back sunscreen bans to protect coral reefs, Florida Today, 1 July 2019 (last accessed 26 April 2021).

Foubert K, Dendooven E, Theunis M, et al. The presence of benzophenone in sunscreens and cosmetics containing the organic UV filter octocrylene: A laboratory study, Contact Dermatitis 2021 (online version ahead of print). DOI: 10.1111/cod.13845

Garner B, Review: Avene Intense Protect SPF50+ sunscreen: All about the octocrylene-gate and the new TriAsorB filter, BTY ALY, March 2021 (last accessed 26 April 2021).

Turgis C, Printemps: grandes marées et retour du soleil, attention aux crèmes solaires périmées, Franceinfo, 28 March 2021 (last accessed 26 April 2021).

Wow! I don’t think you missed a beat with this article. Great work. Thank you.

Wow, Michelle … thank you so much for doing such a thorough review. It’s unfortunate that even peer-reviewed work is not always trustworthy. I ran into a similar situation with an article in the psychology field.

I’m a professional academic. Calling people you disagree with propaganda in a journal article is an ad-hominem beta, loser move.

I don’t have My PhD yet, but I whole heartedly agree that bad mouthing other professionals (especially those outside the area of the author’s expertise) is inappropriate & unprofessional.

I’m not an academic, but I’ve been a publisher of academic journals for 16+ years and have laid out hundreds of peer-reviewed articles. Not once have I ever seen authors talk about other professionals like that. Unreal.

Octocrylene is an active ingredient in Ultra Violete sunscreen lip balm….not to be eaten? Hmmmm…

Well, you’re not going to be applying 3 x 18 g of it on your lips every day…

Well argued, well presented. Great job of putting the literature in context and explaining it to the public.

This is always a challenge for health care professionals. You really aced it!

Thank you Michelle. Enlightening reading.

Thank you so much for this. The fact they called you a propaganda blog is just plain sad especially because you are an expert outside the area of the author’s field in the first place.

Thank you for the evidence-based info.

Fun fact – we have a holiday home in Banyuls and I volunteered in the Observatoire Oceanique many years ago, back when I planned studying marine biology rather than medicine. Way to come full circle here 🙂

I actually found this page and your YouTube channel because I’m reading this study. I am a medical researcher in cosmetics in cosmaceuticals, and then the first few lines made it clear that “benzophenone is a known carcinogen,” which immediately made me suspicious. I have researched at least 10 benzophenones (as there is definitely more than 1) and some had mutagenic properties, but others didn’t. And, the ones of high molecular weight don’t really interact with or absorb into the skin at all… making their initial premise confusing.

I’m glad I came to the same, very confused, conclusion as well. I have to include this study in my writing on octocrylene, but now I have some extra context.

Thanks!

Brilliant explanation! Thank you for your time and effort on this.

If there’s no data/research in humans on how benzophenone could cause cancer in humans, it does not necessarily means that it is safe. We do not need to ignore the fact it can be true. Therefore, we should require more transparency, honest and comprehensive research from the regulatory agencies

The EFSA and WHO have detailed information in their reports – they base their conclusions on the current evidence. It might be reassuring to read their reports to understand how risk assessments are performed.

Um, you are my favorite.